Joseph Alois Schumpeter.

(V.F. voir plus bas)

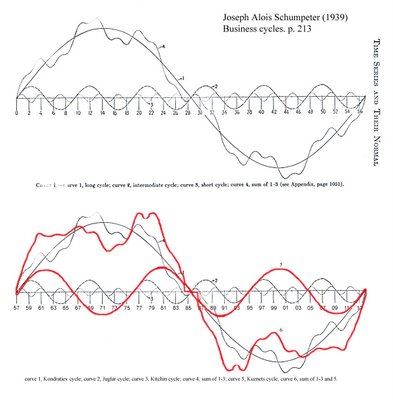

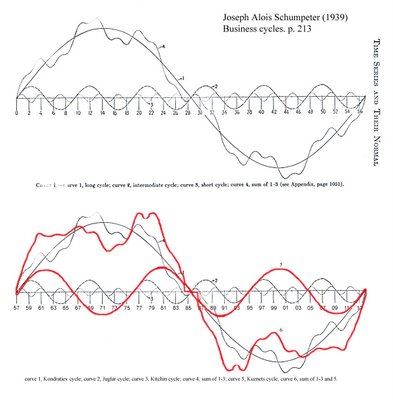

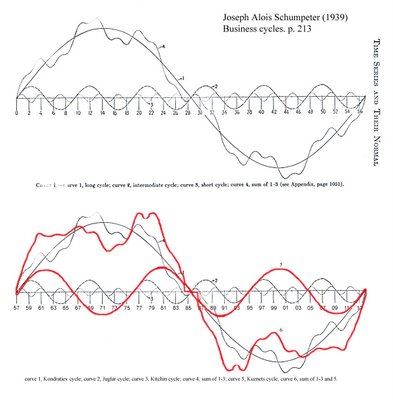

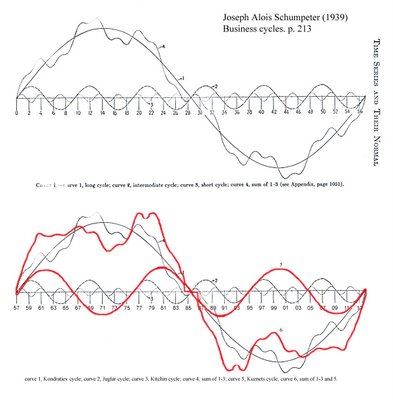

In 1939 Simon Kuznets had not studied the cycle which was to take his name. I have added it and drawn a new average curve. Curiously, if the beginning of the curve is placed in 1900, historical events seem to fit into place quite precisely. E.g. WW1 and the oil crisis in 1973, or the 1929 and 1987 stock market crashes. This correspondence in time suggests that the long wave is influenced somehow by the dominant source of energy, but its regularity must be explained by something with a perfect time table, such as borrowing.

October the 8th, 2008.

I started by imagining that Schumpeter’s time scale began in the year 1900. This conveniently placed the 1929 stock market crash on a short and peculiar up and down phase (middle of curve 4), and 58 years (instead of 57?) later was the stock market crash of 1987. Other coincidences of growth and recession, of war and peace, seemed to occur, but something was lacking.

I was already convinced that business cycles were linked to, and even caused by, debt and credit cycles. By this I mean that growth in the value exchanged on the market must be fuelled by a proportional growth in the value of the means of payment (credit and cash) in circulation. The long cycle corresponded to 30-year debts, the intermediate cycle to 5-year debts, and the short cycle to a mix of 1-year and 2-year debts. Now 10-year debts, treasury bonds in particular, were absent, as was the curve of Simon Kuznets’ later work on housing cycles. So I decided to add a 19-year cycle and draw the resulting curve 6. This gives a more precise picture of past events and, one may suppose, of future ones.

The complete globalisation of debt cycles is quite recent. The timing of debt cycles depends on who is emitting the credit. That means that the main banking system gives the cue to all those in its sphere of influence. Venice, Amsterdam, London have to a certain extent filled this function in the past. It was after WW2 that New York became the western world’s purveyor of credit, with the US dollar as its currency. A predominance that was reinforced when the gold standard agreement reached at Bretton Woods in 1944 was abandoned in 1971.

However, the Soviet Union and China, and their satellite states remained outside this global structure, until the late 1980’s and the early 1990’s. Now that they are an integral part of it, they are swept by the same wave system.

Why choose 1900 as the starting point for all the curves? In the absence of more precise material on debt cycles, why not? The coincidences are there. What of other debts of intermediate terms, 3, 7, 15 or 25 years? That would need software know-how I don’t have. And, for a really precise calendar of events, the yearly volume of debt of each of the cycles would have to be considered. That may not be statistically possible.

20/11/08

J’ai pris ces courbes, qui ne représentent qu’une échelle de temps, et je les ai fait commencer en 1900. Les guerres mondiales correspondaient assez bien et le krach de 1929 aussi. Puis j’ai comparé avec le cycle suivant qui débute en 1957. Là aussi la crise pétrolière arrivait à point, ainsi que le krach de 1987. Mon idée était que les courbes étaient celles de la croissance de la demande solvable, alimentée par la dette et le crédit, le crédit court de 1 et 2 ans, ou de 5 ans, et la dette longue de 30 ans. Il manquait le dette de 10 ans qui se rapproche du cycle étudié par Kuznets. Je l’ai rajoutée en rouge(5) et j’ai redessiné la somme des quatre courbes(6). Le résultat correspondait mieux aux événements du passé et il annonçait une période de stagnation (avec inflation?) pour les trois années à venir. La dernière fois, en 1951, c’était le début de la guerre froide et d’une nouvelle étape dans les “bienfaits du colonialisme”.

Pourquoi démarrer le modèle en 1900? Pourquoi pas, puisque la date semble convenir? Par ailleurs, les courbes de la dette n’ont pas cette parfaite régularité. Avec les données exactes des endettements mondiaux, le calendrier serait forcément plus précis.

In 1939 Simon Kuznets had not studied the cycle which was to take his name. I have added it and drawn a new average curve. Curiously, if the beginning of the curve is placed in 1900, historical events seem to fit into place quite precisely. E.g. WW1 and the oil crisis in 1973, or the 1929 and 1987 stock market crashes. This correspondence in time suggests that the long wave is influenced somehow by the dominant source of energy, but its regularity must be explained by something with a perfect time table, such as borrowing.

October the 8th, 2008.

I started by imagining that Schumpeter’s time scale began in the year 1900. This conveniently placed the 1929 stock market crash on a short and peculiar up and down phase (middle of curve 4), and 58 years (instead of 57?) later was the stock market crash of 1987. Other coincidences of growth and recession, of war and peace, seemed to occur, but something was lacking.

I was already convinced that business cycles were linked to, and even caused by, debt and credit cycles. By this I mean that growth in the value exchanged on the market must be fuelled by a proportional growth in the value of the means of payment (credit and cash) in circulation. The long cycle corresponded to 30-year debts, the intermediate cycle to 5-year debts, and the short cycle to a mix of 1-year and 2-year debts. Now 10-year debts, treasury bonds in particular, were absent, as was the curve of Simon Kuznets’ later work on housing cycles. So I decided to add a 19-year cycle and draw the resulting curve 6. This gives a more precise picture of past events and, one may suppose, of future ones.

The complete globalisation of debt cycles is quite recent. The timing of debt cycles depends on who is emitting the credit. That means that the main banking system gives the cue to all those in its sphere of influence. Venice, Amsterdam, London have to a certain extent filled this function in the past. It was after WW2 that New York became the western world’s purveyor of credit, with the US dollar as its currency. A predominance that was reinforced when the gold standard agreement reached at Bretton Woods in 1944 was abandoned in 1971.

However, the Soviet Union and China, and their satellite states remained outside this global structure, until the late 1980’s and the early 1990’s. Now that they are an integral part of it, they are swept by the same wave system.

Why choose 1900 as the starting point for all the curves? In the absence of more precise material on debt cycles, why not? The coincidences are there. What of other debts of intermediate terms, 3, 7, 15 or 25 years? That would need software know-how I don’t have. And, for a really precise calendar of events, the yearly volume of debt of each of the cycles would have to be considered. That may not be statistically possible.

20/11/08

J’ai pris ces courbes, qui ne représentent qu’une échelle de temps, et je les ai fait commencer en 1900. Les guerres mondiales correspondaient assez bien et le krach de 1929 aussi. Puis j’ai comparé avec le cycle suivant qui débute en 1957. Là aussi la crise pétrolière arrivait à point, ainsi que le krach de 1987. Mon idée était que les courbes étaient celles de la croissance de la demande solvable, alimentée par la dette et le crédit, le crédit court de 1 et 2 ans, ou de 5 ans, et la dette longue de 30 ans. Il manquait le dette de 10 ans qui se rapproche du cycle étudié par Kuznets. Je l’ai rajoutée en rouge(5) et j’ai redessiné la somme des quatre courbes(6). Le résultat correspondait mieux aux événements du passé et il annonçait une période de stagnation (avec inflation?) pour les trois années à venir. La dernière fois, en 1951, c’était le début de la guerre froide et d’une nouvelle étape dans les “bienfaits du colonialisme”.

Pourquoi démarrer le modèle en 1900? Pourquoi pas, puisque la date semble convenir? Par ailleurs, les courbes de la dette n’ont pas cette parfaite régularité. Avec les données exactes des endettements mondiaux, le calendrier serait forcément plus précis.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home